For generations, the prevailing wisdom was simple: if the highway bypasses your town, your town dies. That belief took root in the 1950s and 60s, when the interstate system cut new ribbons of asphalt across the country. Many small towns, unprepared for the change, lost their passing trade almost overnight. Shops closed. Gas stations shuttered.

But it wasn’t the bypass alone that killed those towns; it was the bypass combined with a fragile or one-pony economies. Once one or two industries moved or shut down, towns that relied heavily on pass-through traffic saw businesses fold, residents leave, and little reason for visitors to return.

THEN VS. NOW; WHY “BYPASS = DEATH” ISN’T THE SAME STORY ANYMORE

1950s–60s Reality:

- Short driving range. Cars needed fuel more often, and they were less comfortable, prompting passengers to want to stop more often.

- Lower speeds. Trips took longer, making roadside stops common.

- Few dining & lodging options. Travelers relied on main-street cafés, motels, and gas stations.

- Limited in-car entertainment. Stopping in town was part of the trip experience.

- Small-town dependency. Many local economies relied almost entirely on passing travelers.

Today’s Reality:

- High fuel efficiency and comfort. Cars can easily go 400+ miles without stopping.

- Highway speeds & access. I-20 and modern highways keep traffic moving around towns.

- Chain convenience. Travelers can stop at highway gas stations without detouring downtown.

- Purpose-driven visits. People come downtown intentionally for events, dining, and shopping.

- Economies are diversified. Healthy towns thrive on local customers, tourism, and regional draw, not random pass-throughs.

WHY THE “BYPASS KILLED OUR TOWN” STORY STICKS AROUND

- It felt sudden. For many communities, the bypass and the downturn happened in the same decade, so the two became linked.

- It’s visible. You can see a new road; you can’t always see deeper economic shifts like factory closures or population decline.

- It’s personal. For business owners who lost customers, the bypass was the most obvious change to blame.

- It was true in some cases. Small towns with no other economic base were devastated – but their fragility, not just the road, was the root cause.

The truth: Healthy, well-planned towns adapt, attract visitors on purpose, and often flourish once heavy truck traffic moves away from their core.

Research from the University of Texas and others shows that in towns with a healthy economy, rerouting heavy trucks often led to more attractive, pedestrian-friendly downtowns.

Each of these has proven that moving truck traffic away can strengthen, not weaken, the city center. For example:

Greenville, South Carolina

- What happened: A highway bridge once ran right through downtown, cutting off its connection to the Reedy River and killing pedestrian life. Removing that bridge and adding a pedestrian-friendly bridge in 2004 helped Greenville reconnect with its river and rekindle downtown vibrancy.

- Why it matters: This transformation paved the way for public spaces like Falls Park and the Swamp Rabbit Trail, turning downtown into a walkable, thriving destination loved by locals and tourists alike.

Oxford, Mississippi

- What happened: By implementing “Complete Streets” policies, making downtown corridors safer and more inviting for walking, biking, and biking, Oxford nurtured a boom in its local economy.

- Why it matters: These efforts helped Oxford become one of the top micropolitan economies in the U.S., with zoning and design reforms driving foot traffic and downtown vitality. Especially for its college community, helping Ole Miss grow as a university by making its setting much more appealing to young people, despite its small size.

Bastrop, Texas

- What happened: While not a bypass example per se, Bastrop adopted progressive land-use policies—including a walkable street grid code—that support sustainable downtown growth.

- Why it matters: These planning efforts preserved Bastrop’s historic character while making future development more fiscally and geographically sustainable—serving as a strong model for Ruston if trucks were rerouted elsewhere.

The kind of through-traffic Ruston gets today does not need to stop. And when they do stop, it’s almost always at chain gas stations or fast-food restaurants along the highway, not the historic downtown.

Additionally, a large part of the traffic is part 18-wheelers, vehicles that can’t reliably stop anywhere in the city core without major detours. What those that do pass through the city core bring:

- Noise and diesel fumes that drown out outdoor music and dining.

- Design restrictions due to federal highway designation that limit city improvements.

- Safety and walkability challenges that discourage foot traffic.

Let’s explore these negative effects further:

Noise Pollution:

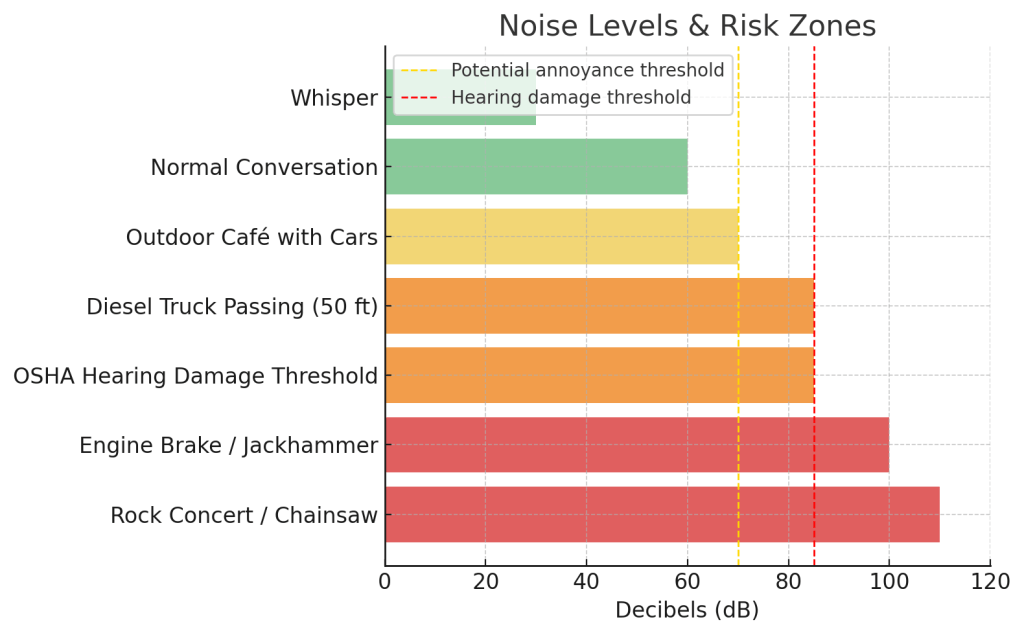

- 70 dB and below: Generally considered safe for the public, but can still be annoying and interfere with conversation or music. Long exposure above 70 dB may cause stress and sleep disturbance.

- 85 dB: Hearing damage risk begins with prolonged exposure (8+ hours per day). OSHA uses 85 dB as the threshold for requiring hearing protection in workplaces.

- 100 dB+: Can cause hearing damage in as little as 15 minutes without protection.

- Passing or accelerating diesel trucks often reach 85–90 dB at 50 feet.

- Engine braking (“jake brakes”) can spike noise levels well above 100 dB for a moment; louder than a jackhammer.

- Idling diesel trucks can emit noise levels of around 85 dB at a distance of 50 feet; that’s as loud as a city bus or a busy urban street.

- Heavy trucks are consistently identified as the loudest and most annoying sources of road noise, often interfering with sleep, reducing the effectiveness of noise barriers, and degrading quieter pavement surfaces.

Air Quality Pollution:

- Nationwide, freight trucks contribute roughly 10% of NOₓ and 12% of CO₂ emissions, and combined transportation-related public health costs are estimated at nearly $47 billion annually.

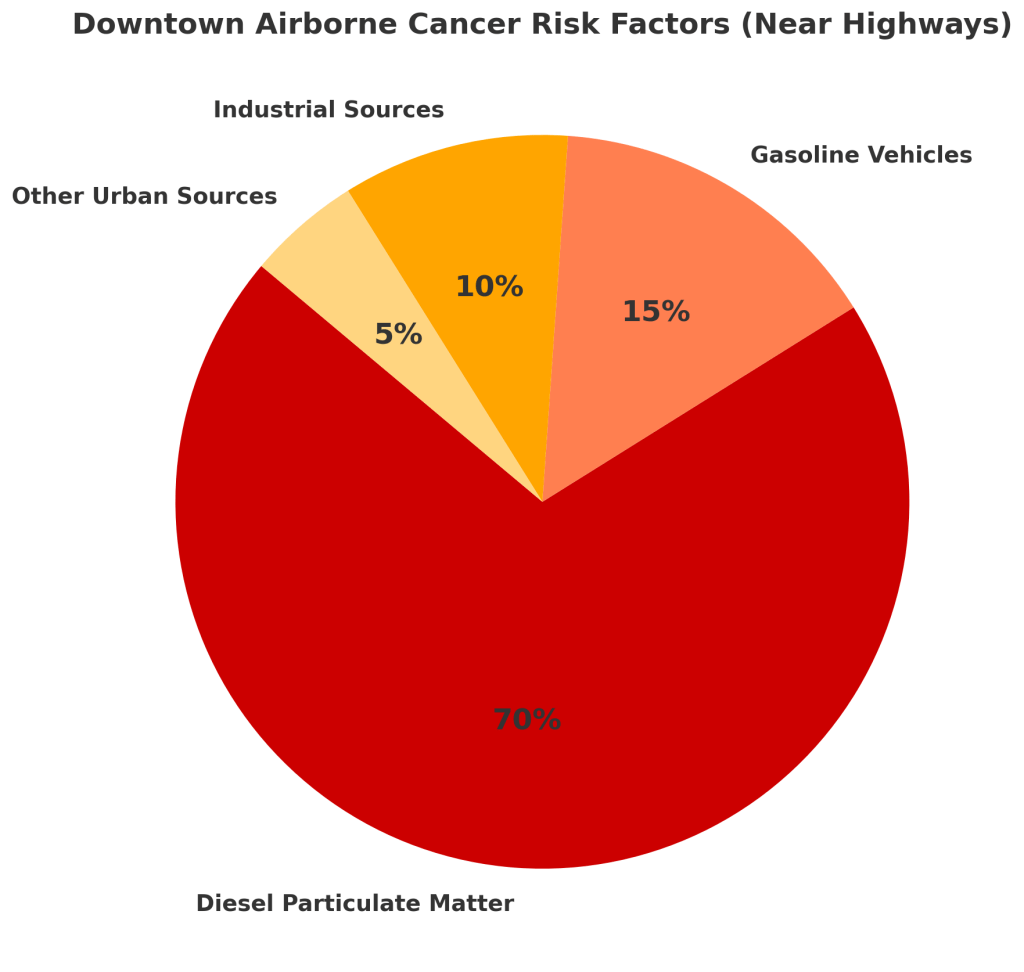

- Diesel exhaust is classified as carcinogenic to humans, associated with lung cancer, asthma, cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality.

- Near heavily used highways, 70% of the airborne cancer risk from toxic air pollutants in 2000 was attributed to diesel particulate matter.

HOW NOISE POLLUTION & DEISEL FUMES AFFECT RUSTON:

Noise levels around 60–70 dB are enough to drown out conversation and strain outdoor seating areas, especially when punctuated with truck engine noise.

Proximity to heavy diesel traffic significantly increases exposure to PM₂.₅ and NOₓ, which can have immediate effects on respiratory comfort and long-term health.

These disruptions and hazards can significantly reduce the appeal of dining, events, and community gatherings downtown.

Design Restrictions around Federally Designated Highways:

Lane Widths & Road Geometry

- Federal/state standards often require wider lanes (11–12 feet) for through-traffic and freight, while pedestrian-friendly streets typically aim for 9–10 feet to slow traffic.

- This makes it harder to narrow lanes for sidewalk expansion, outdoor seating, or landscaped medians.

Speed Limits & Traffic Flow

- Highways are engineered for higher speeds, so reducing speed limits for a more walkable feel may require state approval.

- Traffic-calming tools like raised crosswalks, speed tables, or sharper curb radii are often prohibited or discouraged.

Signal Timing & Intersection Changes

- The city can’t freely change signal timing to prioritize pedestrians or event closures if it slows down through-traffic beyond state/federal tolerances.

Restrictions on Streetscape Changes

- Adding trees, decorative lighting, benches, or planters in certain buffer zones can violate clear zonesafety requirements for highways.

- Curb extensions (“bulb-outs”) that shorten pedestrian crossings are sometimes disallowed because they change the “effective width” of the travel lane.

Limited Flexibility for Event Use or Closures

- Hosting parades, markets, or street festivals may require special state permits and traffic control plans every time, which can be expensive and bureaucratically slow.

Signage & Branding

- Sign design, size, and placement have to meet state and federal highway manuals — limiting the city’s ability to use more charming, small-scale, or creative signage that fits downtown character.

Traffic as a Barrier to Walking:

- Nearly 25% of U.S. adults report that traffic is a barrier to walking where they live, or the distance they are comfortable walking from a parking spot to their destination.

• Of these, 79% point to vehicle speed as a major concern.

- Heavy vehicles are associated with a 2.4% increase in the pedestrian fatality rate in metropolitan areas; replacing light trucks with cars could have prevented thousands of deaths.

HOW DESIGN RESTRICTIONS & SAFETY ISSUES DOWNTOWN AFFECTS RUSTON:

High-speed, heavy-truck traffic makes sidewalks feel unsafe or uninviting, reducing foot traffic for downtown businesses.

Increased crash risk and reduced walkability discourage families and pedestrians from lingering or visiting in the first place.

Reclaiming downtown streets for people, through improved sidewalk design, lower traffic volumes, and safer intersections, can boost both safety and economic vitality.

If a By-pass was going to kill Ruston, it would have been when I-20 blasted an unhindered path right by Ruston decades ago, diverting the majority of east–west travelers away from Hwy 80 and the city center. Ruston survived, and even grew, because our economy is not built on random pass-through drivers.

What Ruston gains if trucks are rerouted:

Finding a bypass route that works for Ruston’s geography and politics could mean:

• A quieter, safer, more walkable downtown.

• Stronger appeal to locals and tourists who choose Ruston as a destination.

• A boost in property values and private investment.

Bypasses don’t inevitably kill small towns, but they can change the business mix. Ruston’s diverse downtown economy, local attractions, and regional draw suggest it’s well-positioned to adapt, possibly even benefit, if truck traffic is rerouted thoughtfully. The goal isn’t just to move trucks, it’s to re-center downtown around people, ambiance, and intentional visits.

THE CHALLENGE ISN’T WHETHER WE SHOULD GET TRUCKS OUT OF DOWNTOWN — IT’S WHERE WE PUT THEM:

- A southern bypass could run uncomfortably close to Grambling, raising concerns about property impacts, environmental justice, and economic overlap.

- A northern bypass could affect Choudrant-area neighborhoods and face pushback from residents who don’t want freight traffic in their backyard.

Methodology of Determining a By-Pass Route:

1. Start with a Transparent Route Feasibility Study

- Partner with LaDOTD and an independent urban planning consultant to model 2–3 possible bypass alignments.

- Study not just engineering costs, but land use, property impacts, and noise modeling for each option.

- Make findings public early to prevent “black box” decision-making rumors.

2. Apply “Least Harm, Most Benefit” Routing Principles

- Prioritize routes along existing transportation corridors (rail lines, utility easements, underused industrial zones) to minimize property takings.

- Avoid splitting neighborhoods or running through high-value environmental or historic areas.

- Consider partial bypasses — where only heavy truck through-traffic is redirected — so passenger cars still have flexible routes.

3. Design the Bypass as a Complete Street for Freight

- Build for trucks: adequate lane widths, gentle curves, good shoulders — so drivers want to use it instead of downtown.

- Include noise berms, tree buffers, and setback requirements for any nearby residential areas to protect quality of life.

4. Make It a Win for Nearby Communities

- Tie bypass construction to infrastructure improvements for affected towns: better local road connections, safer crossings, or new greenways alongside the road.

- Offer economic offsets (like small business grants or signage programs) to nearby communities to ease concerns about losing visibility.

5. Secure Funding Without Gutting Local Budgets

- Blend state/federal highway funds with grants for safety, freight efficiency, and even environmental impact mitigation.

- Explore federal INFRA or RAISE grants, which reward projects improving freight flow while protecting communities.

6. Pair the Bypass With a Downtown Reinvestment Plan

- Don’t just move the trucks — fill the vacuum.

- Use the reduction in heavy traffic as the cue for sidewalk expansions, outdoor dining incentives, public art, and event programming to draw people back in.

CONCLUSION:

- Bypasses aren’t universally harmful — impacts depend heavily on the town’s economic health, local strategy, and adaptability.

- Benefits go beyond reducing traffic — quieter streets, lower emissions, and improved safety can enable better downtown experiences.

- Economic structures matter — towns with diverse economies or visitor draws can often pivot effectively post-bypass.

The real danger isn’t in bypassing our town; it’s in clinging to outdated fears while our human-scaled downtown competes with the negative effects of system not designed to be people-friendly. We have the chance to make downtown a place people seek out, not pass through, but only if we plan for the Ruston of tomorrow, not the unexamined fears of yesterday

.

This study was compiled by Laura Hunt Miller, August 11, 2025

If you’d like to explore further research on this topic, here are a few studies:

1. University of Texas at Austin – Center for Transportation Research: Economic Effects of Highway Relief Routes on Small- and Medium-Size Communities

This comprehensive study used case studies of 10 Texas towns to explore both positive and negative economic effects. It found that while bypasses generally reduced traffic through downtowns, resulting in noise and safety benefits, the impact on local businesses varied based on community characteristics and development along the bypass route.

2. Hill Country Alliance Summary of UT study findings

Using econometric analysis, this study showed that bypass investments had positive impacts on manufacturing employment at the city level, and also improved employment and wages across the county.

3. Kansas State University: Economic Impacts of Highway Bypasses in Kansas

A regression study found that bypass construction had no statistically significant effect on total employment in most towns examined. Business owners reported mixed impacts—while they felt sales declined, employment largely stayed the same.

4. Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (Australia): Economic Impacts of Bypasses

In Berrima, tourism blossomed when its historic charm was preserved without heavy traffic. Mittagong initially saw slight economic setbacks, but expectations are for a mild positive impact as travelers realize the town is quieter and more appealing.

Leave a comment