This article was first published in the Lincoln Parish Journal, Sept. 30, 2025

Part 1: Urban Green Spaces

Not long ago, a number of mature trees were removed from a downtown lot in Ruston. And boy was there a hub-bub about it.

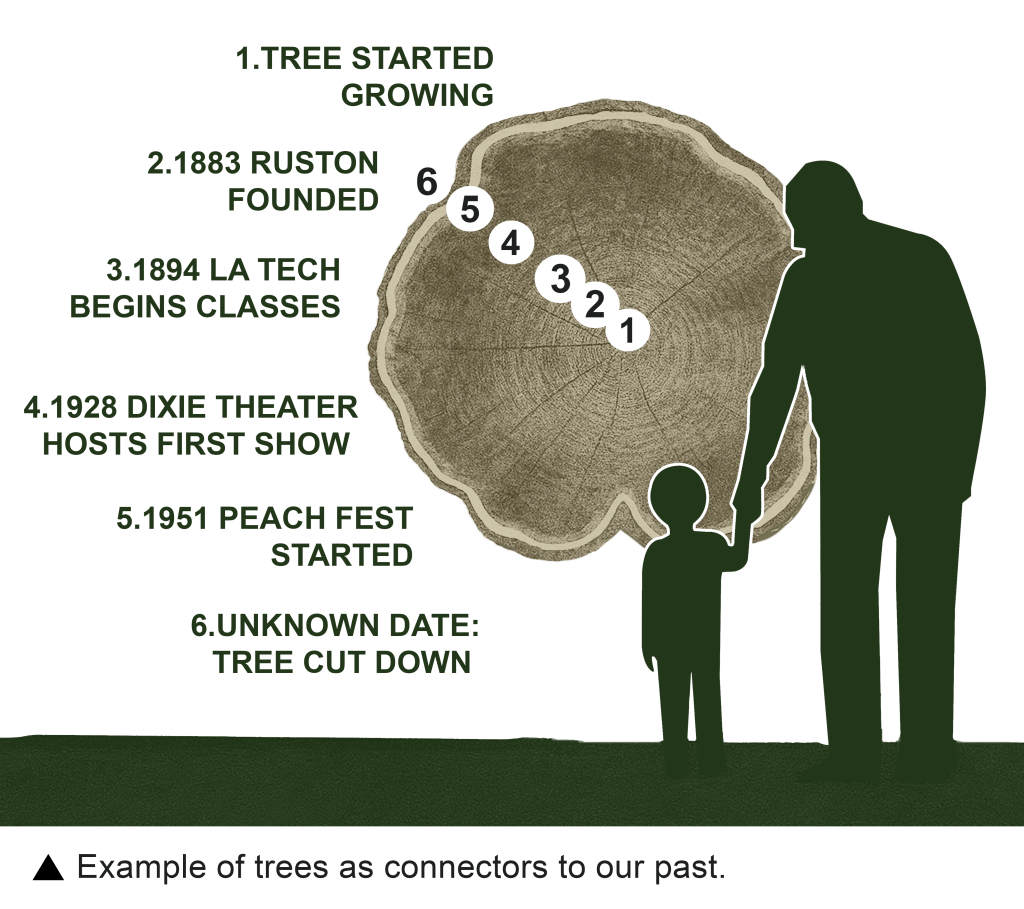

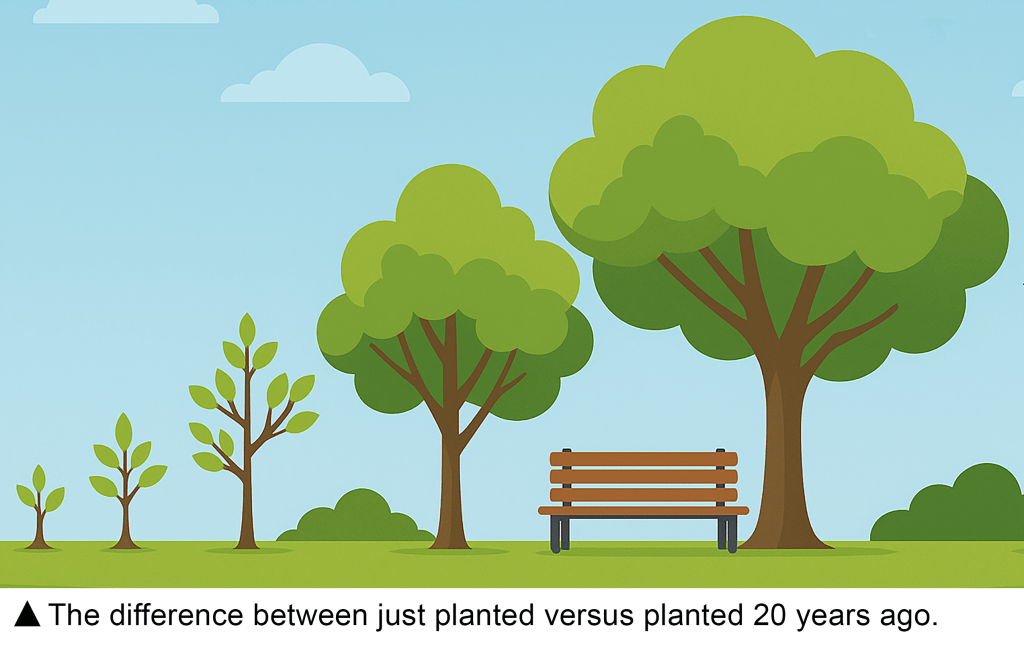

While the strong reaction came as a surprise to some, others understood both sides of the situation and felt the loss. When familiar landscapes change in ways we perceive as negative, especially in a communal space like our downtown, it can feel like our own memories have been compromised, or that we have lost a connection to those who came before us in that same space. Especially when the loss involves something like a mature tree that cannot be regrown in our lifetime.

Now what’s done is done, so let’s leave the pitchforks in the shed, and focus on how best to move forward—together—as both community developers and citizens.

After all, real progress isn’t about arguing over who was right or wrong, it’s about forging new paths with a more unified vision for everyone. And the future I hope we can begin to build is one where we think differently about our urban trees and green spaces.

Between 1950 and today, generations of urban trees have been lost. Why? Because green elements are typically treated as ornamental or non-essential, the stuff that gets tacked on at the end of a project if there’s time or money left. Or they are seen as obstacles that have to be cleared to get anything done. This mentality stems from a mix of historic trends and economic pressures that shaped the way our nation was formed.

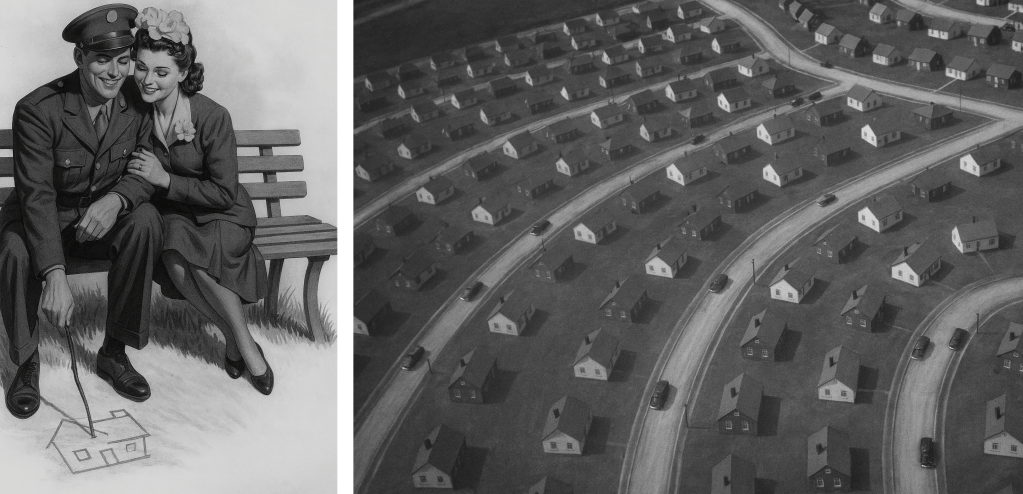

After World War II, the U.S. saw a massive push for civil engineering–led suburban expansion, highway construction, and commercial sprawl. The priority was speed, affordability, and accommodating cars, not ecological balance. If a line-item didn’t support those goals, it often wasn’t included.

In an increasingly litigious country, trees also became something developers and business owners grew hesitant to make room for as the risk-reward equation was not encouraging. Working around trees introduced the chance of root damage and potential liability from dying trees, construction delays, or even accidents and code violations. Clearing the site entirely became the safer bet, at least on paper (ironically). Over time, many cities had to step in with ordinances or preservation incentives just to keep green spaces from vanishing altogether.

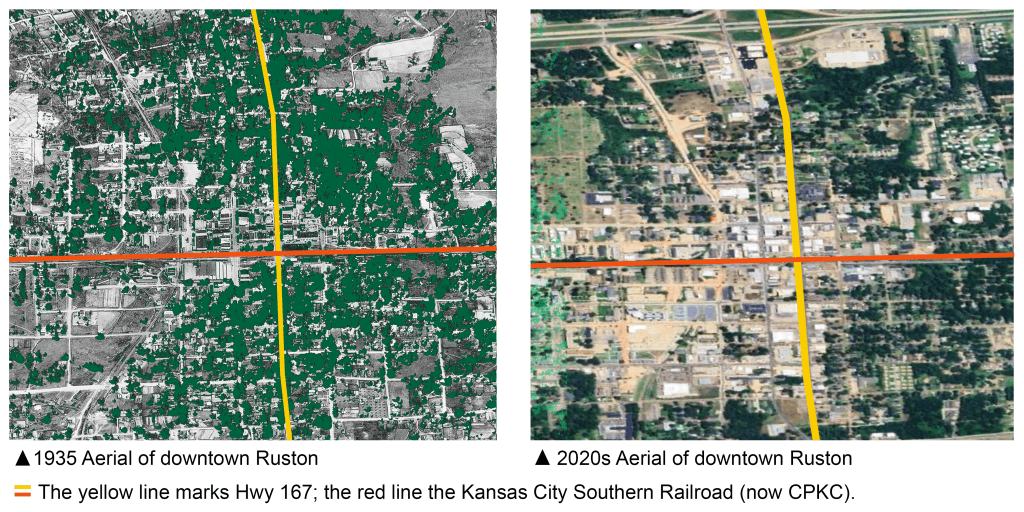

Our own downtown shows a distinct loss of greenery over the past century as the image above demonstrates. This is to be expected as an area populates with buildings, roads and the other infrastructural needs that come with growth. But now that we’re closer to 2050 than 1950, do we still want to elevate practices that leave our urban environments more barren than shaded? Can we find a way to support growth, business, and green spaces?

In the second part of this article, we’ll explore the modern benefits of urban greenery and the methods cities are using to incorporate more green back into their communities.

Part 2: Investing in our Tomorrow

Last time we looked at how and why so many of our urban green spaces have been lost. Now, let’s explore why, and how, we can bring them back. Greener cities aren’t just powered by “made in the shade” vibes, they are inspired by measurable economic, social, and environmental returns.

Economic Benefits:

• Proximity to green, shaded areas boosts both residential and commercial property values by 7–25% according to research from the U.S. Forest Service and the National Recreation and Park Association.

• Shoppers spend 9–12% more time in shady, walkable retail areas, increasing local sales revenue according to studies cited by the Urban Land Institute and EPA Smart Growth Program.

• Shade trees lower peak cooling costs by up to 30% for adjacent buildings according to data from the U.S. Department of Energy and American Forests.

• Street trees extend the lifespan of roads and sidewalks by reducing heat-related damage and UV degradation according to the U.S. Forest Service and Federal Highway Administration.

• Green downtowns attract events, visitors, and businesses, contributing to revitalization and new growth according to studies from the Urban Land Institute and American Planning Association.

• According to the U.S. Forest Service, urban greenery generates $18.3 billion annually in air cleansing and energy savings—roughly a $2 return for every $1 invested in green infrastructure.

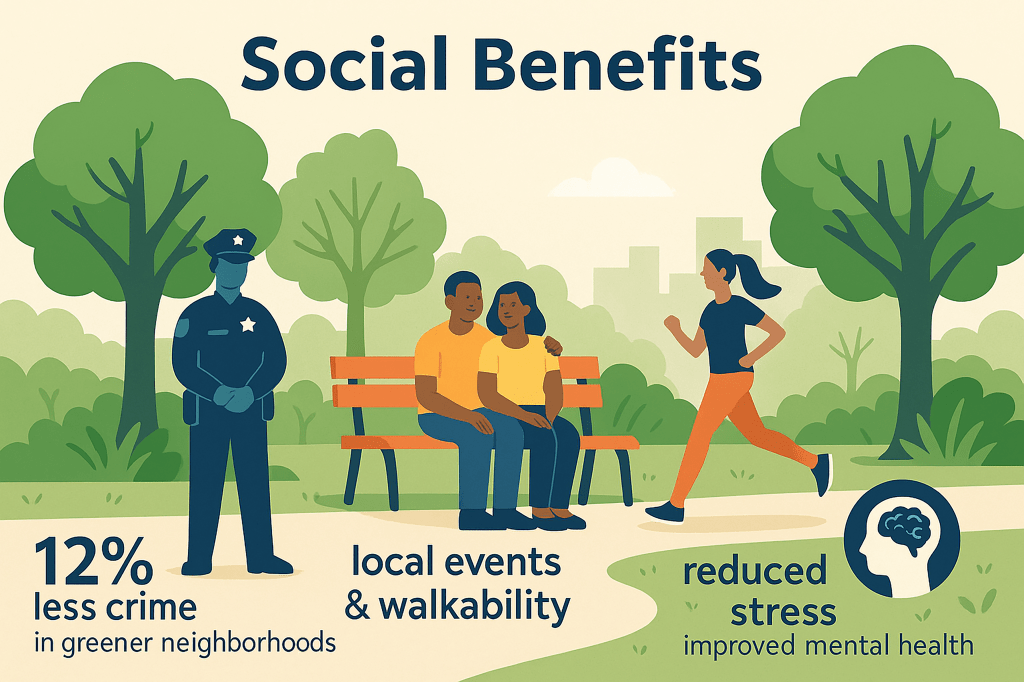

Social Benefits:

• Greener neighborhoods report up to 12% less crime, as well-maintained spaces encourage natural surveillance via community presence, according to research published in Environment and Behavior and supported by the U.S. Forest Service.

• Trees invite people to linger longer, supporting local events, walkability, and community bonding, according to studies from the University of Washington’s Green Cities Research Alliance.

• Access to nature improves mental health, reducing stress and boosting mood, focus, and emotional resilience, even in small doses, according to research published in Frontiers in Psychology and supported by the American Psychological Association.

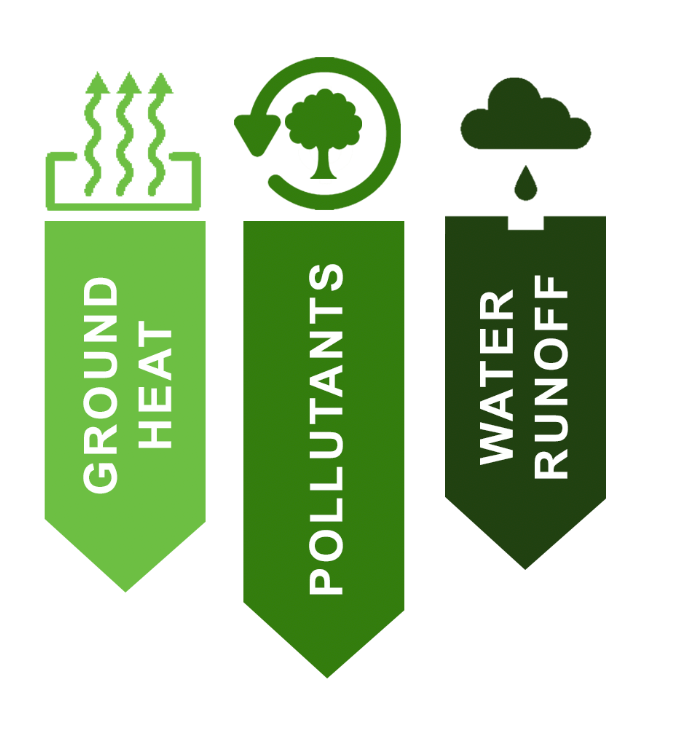

Environmental Benefits:

• Tree canopies cool the built environment by 10–15°F, lowering urban heat island effects across entire districts, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

• Trees absorb and store carbon, helping mitigate climate change, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

• They filter pollutants, reduce smog, and dampen noise, improving overall air and sound quality, according to the EPA.

• Tree roots reduce stormwater runoff, protecting water quality and relieving burden on drainage systems, also reported by the EPA.

When you add it all up, cooler streets, lower crime, stronger property values, cleaner air, it’s clear that trees should be considered more than aesthetic extras; they can be integral infrastructure.

So what kind of policies are cities using to incorporate green infrastructure? Here are a few examples:

Tree Canopy Inventory & Assessment — Goshen, Indiana

Goshen conducted a full tree inventory to understand what they had and what risks their trees faced (disease, pests, climate threats). From that, they built a plan to protect, plant, and maintain based on current data. This kind of assessment-first approach is often what differentiates “just adding trees” from strategic investment.

Link to study:

Tree Mitigation Banking — Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville requires new construction to plant or preserve a minimum number of trees agreed upon by community members. In cases where preservation on site is not possible, they use a “tree bank” model (essentially mitigation banking) so that tree loss is offset elsewhere in the region.

Public And Private Partnerships— Chicago, Illinois

Chicago is a strong example of a city using coordinated public and private efforts, for example, offering matching funds for building green infrastructure like bioswales, permeable surfaces and rain gardens on public property to help manage stormwater naturally. They also operate a “Tree Ambassador” program that trains volunteer citizens to identify tree species and help locate new planting sites to expand the urban canopy.

Link to study:

Tree Cities— Throughout Louisiana

Louisiana has 12 certified “Tree City USA” communities, but not one lies north of Alexandria. The Tree City designation, offered by the Arbor Day Foundation, recognizes cities that meet four basic standards: maintaining a tree board or department, having a community tree ordinance, spending at least $2 per capita on urban forestry, and holding an annual Arbor Day observance.

Becoming a Tree City is more than a title, it signals a commitment to long-term improved quality of life. It also opens the door to funding opportunities, technical support, and partnerships that can help a town grow greener.

Links to study:

https://www.arborday.org/our-work/tree-city-usa?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Making these kinds of programs work locally doesn’t require an all-or-nothing approach. We can start small; pilot projects like tree plantings or shaded parklets sponsored by school groups, churches, businesses, or social clubs are great community activators, like the butterfly garden downtown.

Green projects can also be bundled with existing efforts like sidewalks, parking lot upgrades, and stormwater work to tap into multiple funding streams. Volunteer labor, in-kind donations, and even city staff time can often be counted as matching funds on grant applications, which makes tight budgets more flexible.

A phased approach that uses early funding to conduct studies or create a planting plan, then apply for larger grants to fund installation and maintenance help make sure plans have long-term value. Greenery needs multi-year care, so planning for maintenance costs from the start, and tracking metrics like survival rates and canopy growth make good plans last. Each success story becomes leverage for the next round of investment.

Today, cities and towns are waking up to what was lost and what can be regained. As the saying goes, “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago; the second-best time is now.”

So yes, the “downtown tree incident” was a painful moment, but hopefully one we can circumvent in the future by investing in shared tools and protocols around resources we all want to grow and protect together.

Leave a comment