This article was first published in the Lincoln Parish Journal, Sept. 19, 2025

Part 1: How Connectivity Empowers Communities

When Shel Silverstein wrote, “There is a place where the sidewalk ends,” he was whimsically referring to a place where our imaginations can run free. In the real world, however, fragmented sidewalks trail off into wild grasses, crumbling curbs, and dusty ditches. They end mid-block, mid-step, and often just short of anywhere useful.

And there’s nothing quite like trying to look dignified while trekking across those unkempt gaps. “Yes, I am temporarily urban hiking on purpose, thank you for asking.”

Around here, we tend to look at people who walk anywhere as if they’re a little looney. The heat, rain and humidity can make walking feel impractical, even masochistic at times. But maybe walking itself isn’t the crazy part, maybe it’s the way we’ve built our cities that is out of alignment.

If you look at images of early American cities, sidewalks were everywhere, and people were using them. As we came to embrace car culture and sprawl, sidewalks became afterthoughts, and the networks people relied on fell into decay.

But not every citizen has access to a car. And even those who do, might like the option of walking along safe, dedicated paths to the places they would like to go sometimes.

The Institute of Transportation Engineers says: complete pedestrian networks are “among the most effective infrastructure communities can invest in.”

Why? Because sidewalks pull far more weight than their simplicity suggests. They:

• Connect people and places, giving families safe routes to school, neighbors the ability to walk and talk, and residents without cars the dignity of mobility.

• Support public health, encouraging daily activity, lowering stress, and making walking a real option for short trips.

• Boost local business, by creating walkable districts that attract more foot traffic, browsing, and more dollars.

• Strengthen community ties, as sidewalks become spaces where people meet and build a sense of belonging.

A great example of a city that takes sidewalk seriously is Oxford, Mississippi. They leveraged sidewalk connectivity around its historic square and university district to create one of the South’s most walkable small cities, drawing both visitors and business vitality. The targeted sidewalk infill along busy corridors also dramatically improved pedestrian safety while opening up access to schools and shops.

Sidewalks may seem insignificant, but their absence leaves a big hole in communities. So how do Ruston’s sidewalks measure up? In Part 2 of this series, we will look at the city’s walkability report card, and why the gaps in our sidewalks are more than inconvenient.

Part 2: Assessing Our Sidewalk Situation

Last time we looked at why sidewalks matter. Now let’s look at how Ruston’s stack up.

Although we try, bless our hearts, Ruston is not a walking-friendly town according to WalkScore.com. The website scores cities from 0-100, zero being a place that is completely hostile to walking, and 100 signaling a true “pedestrian paradise.” Ruston has a 25 out of 100.

This rating places us firmly in the “car-dependent” category, meaning most errands require a car, even for short distances. Sound familiar?

Towns with a score of 25 typically have gaps in 50-75% of their walking paths to basic amenities. To feel walkable, towns need 80–90% continuity on key corridors, with continuous sidewalk on both sides of the most traveled routes.

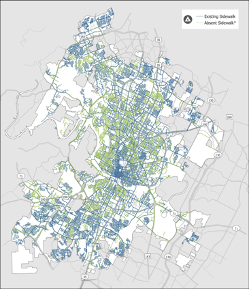

This map shows Ruston’s amenities, and a color scale from WalkScore.com that refers to how accessible they are by sidewalks. Areas outside of the color range are considered not accessible by sidewalk.

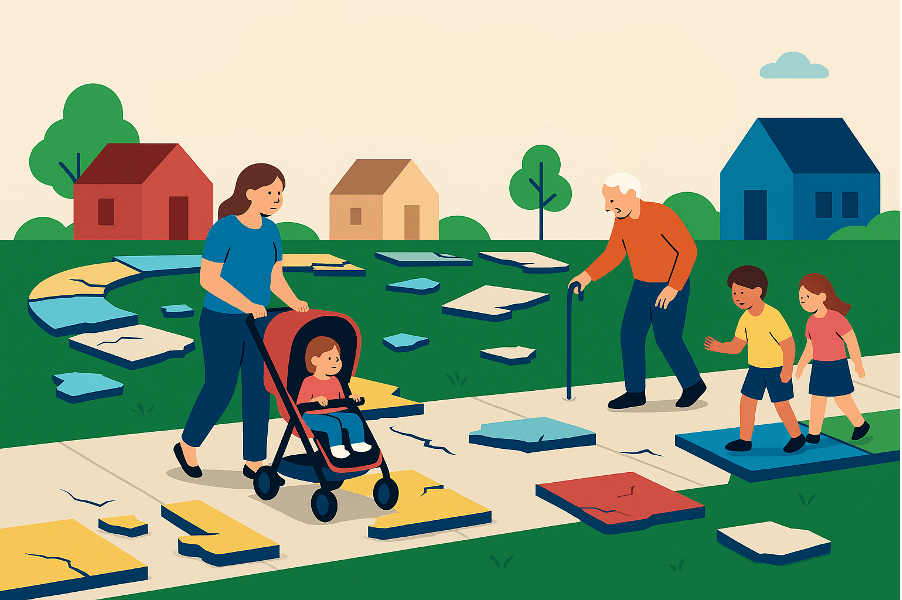

Those numbers aren’t abstract. They show up in everyday frustrations:

• Caretakers having to push strollers into busy streets or over rough terrain when sidewalks suddenly end.

• Students picking their way along muddy shoulders or cutting across yards just to get to class.

• Seniors and people with disabilities facing literal dead ends in what should be public rights-of-way.

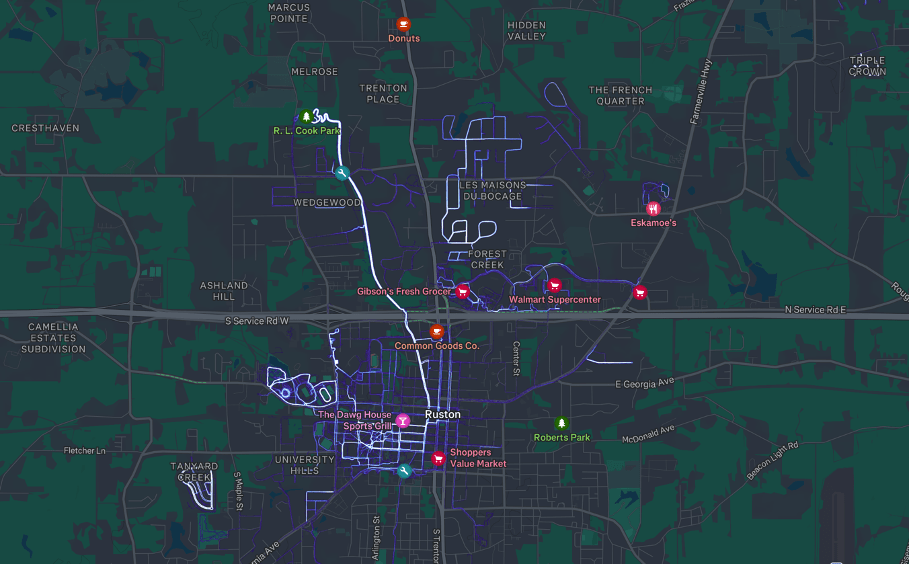

The fitness app Strava, designed to map its users’ workout paths, shows that the most used walking and running routes in Ruston cling to a handful of corridors. The rest of the city appears to be void of areas that feel safe or feasible to walk.

Strava walking paths heatmap of Ruston; the lighter the path, the more it is utilized. This map certainly demonstrates, “if you build it, they will come,” with the Rock Island Greenway showing the most use.

This isn’t just a sidewalk gap. It’s a connectivity gap. Every missing link is a barrier to health, independence, economic vitality, and to the simple dignity of being able to move safely through one’s own hometown on foot.

I’m fortunate to live in a neighborhood with streets wide enough for both walkers and cars. In fact, many non-residents drive here just to walk. When drivers speed through though, especially when our kids are with us, an inevitable tension arises.

That’s the difference between incidental walking space and intentional walking space. Wide streets may function as a stand-in for sidewalks, but they can fail to carry the same sense of safety. Every step in a non-designated walking path depends on trust; trust that drivers will slow down, trust that accidents won’t happen.

A fragmented network doesn’t just make walking unpleasant; it makes it nearly impossible for many people. So what can we do about it? In Part 3, we’ll explore proven strategies towns are using to stitch their sidewalks back together.

Part 3 –Strategies for a Pedestrian-Friendly Places

Ruston could use more pedestrian-friendly paths, but what is the best way to go about filling the gaps? Here are some of the best practices:

1. Continuity and Connectivity

Cities like Austin and Oxford maintain “connectivity maps” to identify the worst sidewalk gaps and set clear priorities for filling them, ensuring resources are spent where they make the biggest impact.

2. Strategic Infill

Many cities integrate infill projects into regular road repairs and new development so that missing links are filled automatically. Ruston has made a goal to utilize this approach, but we still have plenty of gaps that need to be closed where there currently are no plans for road improvements.

3. Accessibility and Design Essentials

Ideally sidewalks should be available for everyone to use, whether walking with friends, pushing a stroller, or using a wheelchair. Federal ADA standards recommend a minimum of five feet in width, with curb ramps and obstacle-free paths.

Cities can map out primary, secondary, and tertiary walking corridors, aiming for a five-foot standard on the main routes and narrowing widths on lower-priority ones to help make the system more feasible to employ.

4. Alternative Materials and Widening What We Already Have

Cities are experimenting with recycled aggregates, reclaimed brick, rubber composites, and other surfaces that cut costs and add character for sidewalk infill projects. And if existing sidewalks are not wide enough, sidewalks have been successfully expanded with material alternatives that transform outdated slivers of sidewalk into safe, functional walkways.

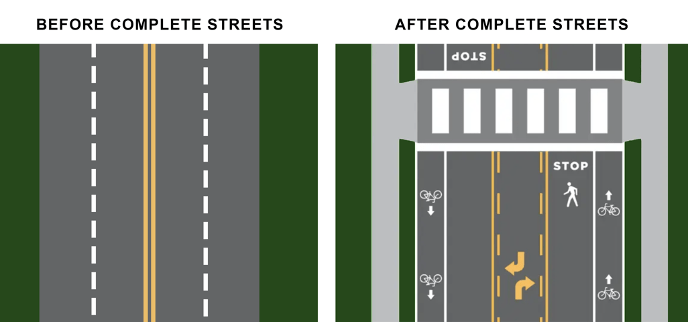

5. Complete Streets and Living Streets

Complete Streets policies require roads to be designed for all users: pedestrians, cyclists and drivers. Living Streets go further, slowing traffic and prioritizing people over vehicles on certain paths with green infrastructure, shared spaces, and social activity. These approaches ensure sidewalks are essential parts of the street and city-wide beautification efforts.

6. Green Infrastructure

Cities are increasingly using permeable paving, bioswales, and shade trees along walkways to manage stormwater, cool urban heat islands, and make walking more pleasant. In our climate, shaded sidewalks could be the difference between unbearable and actually inviting. Imagine that.

7. Community Placemaking

Sidewalks don’t just move people; they are where human interactions take place. Pop-up crosswalks, murals, and tactical improvements shift sidewalks from forgotten strips to beloved parts of community life.

8. Shared Streets

If a neighborhood resists adding sidewalks, it can create a shared street by slowing traffic and adding landscaping to make pedestrians feel safer. The difference, again, comes back to intent: sidewalks make walking reliable, while shared streets make it conditional.

With a thoughtful mix of strategies Ruston could start closing its connectivity gaps one block at a time. But how do we pay for it? In Part 4, we’ll look at funding strategies and partnerships that can lead to a safer, more walkable town.

Part 4 – Funding the Future of Ruston’s Sidewalks

We’ve walked through why we need sidewalks and how we can integrate more, but none of that happens without the big question every city faces: how to pay for it.

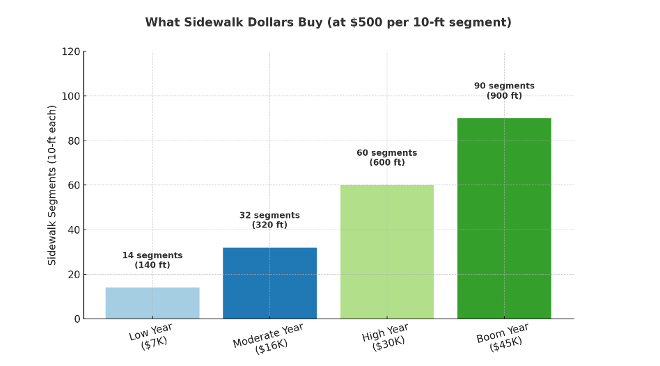

Filling a 10-foot by 5-foot sidewalk gap with concrete costs around $500. There are other material alternatives, but however you go about it, the costs add up across a city-wide network.

Small towns have found ways to fund sidewalk networks without breaking their budgets though:

1. Pair Sidewalks with Road Work

The most cost-effective approach is one we discussed earlier: whenever street work is done, sidewalks go with it. Building sidewalks as part of routine road maintenance keeps costs down and ensures steady progress. Ruston is already doing this, so check!

2. Tap Federal and State Grants

Programs like Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A), Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE), and Louisiana’s Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP) provide funding for pedestrian and bike projects.

Ruston’s 2026 proposed Capital Budget includes $33 million for road and transportation improvements, almost half of which is covered by federal funds via grants. Good job Ruston! Let’s see if we can do even better than that.

3. Explore Local Mechanisms

Many communities create dedicated sidewalk funds through modest impact fees on new development, bond programs, or sales tax allocations. For example, Van Buren, Arkansas established a Sidewalk Construction and Maintenance Fund by setting aside $0.03 per square foot of all building permit fees. This continual revenue stream supports both new sidewalks and upkeep based on the total square footage permitted each year.

4. Build Partnerships

Some universities, health foundations, and civic groups co-fund and offer grants for sidewalk projects. Local businesses can also adopt sidewalk corridors, or implement things like Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)to help fund projects as well.

Pedestrian networks may look like modest infrastructure, but they signal something profound: a community that values accessibility, health, and shared public life. In short, a resilient and inviting place to live.

Let’s create the kind of community we want for our children: one where sidewalks don’t just end, but where something better begins.

Leave a comment