This article was first published in the Lincoln Parish Journal, December 15, 2025.

PART 1: Where Did Our Peace and Quiet Go?

As I walk outside of my house and sit on the back porch, I settle in to listen to the peaceful sounds of local wildlife in the early dusk. But instead, I hear the roaring of an 18-wheeler or modified muffler coming down Highway 167.

As towns grow, they can grow louder. Brighter. Harsher. Due to a series of developments that can create a negative cumulative effect.

This series explores two intrusions that can diminish a community’s shared quality of life: light and noise pollution.

Noise pollution is unwanted or harmful sound that interferes with normal activities like sleeping, relaxing, working or even thinking. It can come from sudden bursts, like a slammed trailer gate on pavement from a yard cleaning crew getting started at 7am, or persistent sources like traffic, trains, or a dog barking constantly that somehow only the owner is deaf to…

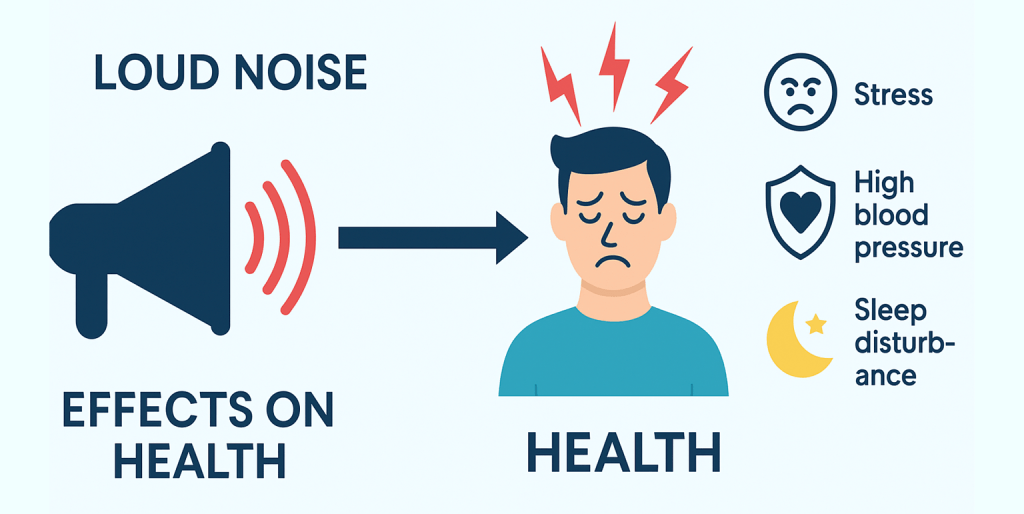

Our bodies respond to disruptive and excessive noise as a form of stress, even when we’re not consciously aware of it. Multiple research resources, from the College of London to Boston University, have shown that prolonged exposure to loud noises can increase cortisol levels, raise blood pressure and disturb sleep, all which contribute to a lower quality of life.

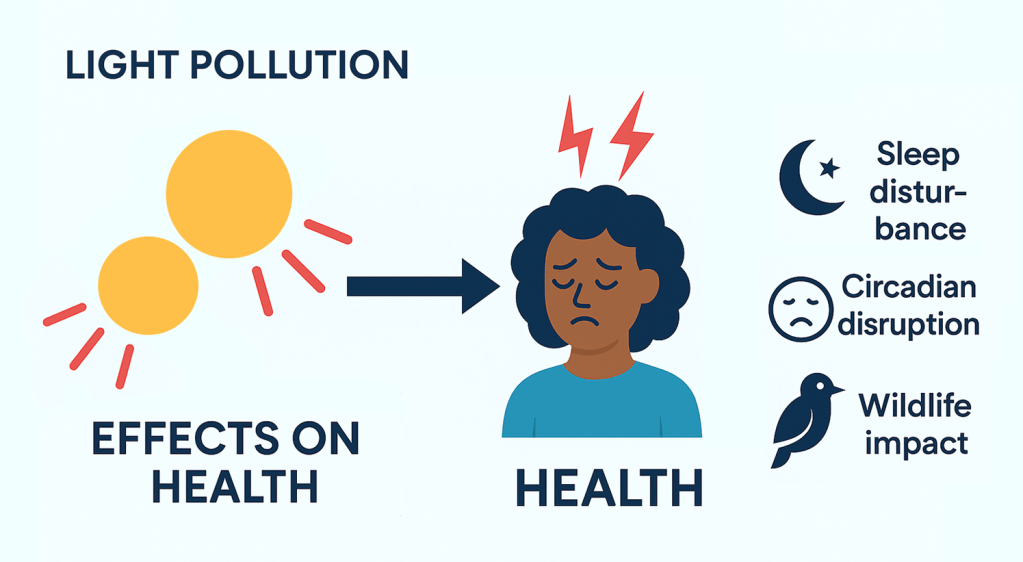

Light pollution on the other hand is excessive, misdirected, or artificial light that disrupts natural darkness. It includes everything from constant parking lots lighting, high-intensity street lights that spill into homes, skyglow that erases the stars, or LED signs that burn through the night.

Light pollution interferes with our sleep by suppressing our natural melatonin production and disrupting our circadian rhythm, and negatively affects wildlife by confusing animals that rely on daylight patterns to tell them when to eat, sleep and migrate.

Let’s take a closer look at these two nuisances, and the ways they affect our community, starting with sound pollution.

Reference dBA Scale.

According to the World Health Organization, the 90-plus decibel volume of traffic that can be heard at any time of the day in our backyard falls well within sound pollution parameters. The constant hum and rumble of traffic is unavoidable, and we live over three and a half football fields off the highway with a good number of mature trees in our neighborhood. But the land is flat.

Noise travels horizontally outward from its source. Think of a traffic lane as the mouth of a megaphone, radiating out horizontally in all directions. Over flat land, especially with hard surfaces like pavement or bare ground, there is little natural absorption. Noise stays low and travels farther, rather than dissipating.

Over flat ground with few sound barriers, sound travels closer to 1,000 ft.

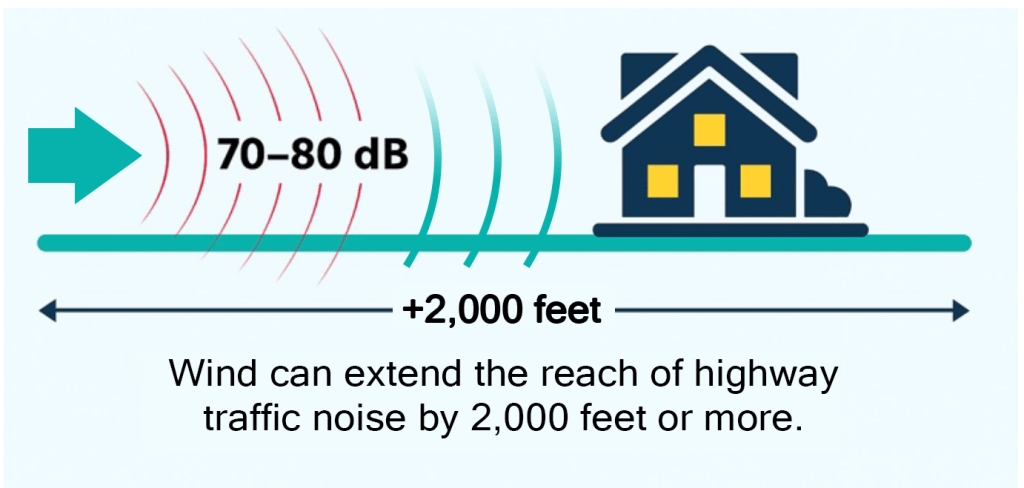

And if there is a strong wind? It carries sound waves even further as sound waves are pushed along the ground. In highly variable or gusty conditions, sound is scattered in multiple directions, causing sound to fluctuate, briefly getting louder or quieter as it spreads.

Without significant elevation changes or natural barriers to block noise, diverting it is a big challenge. According to the Federal Highway Administration, achieving a 50% reduction in noise requires a combination of elevated earth berms, dense evergreen buffers, and sound-dampening surfaces, none of which currently exist in Ruston at scale.

Let’s consider this impact alone to our area.

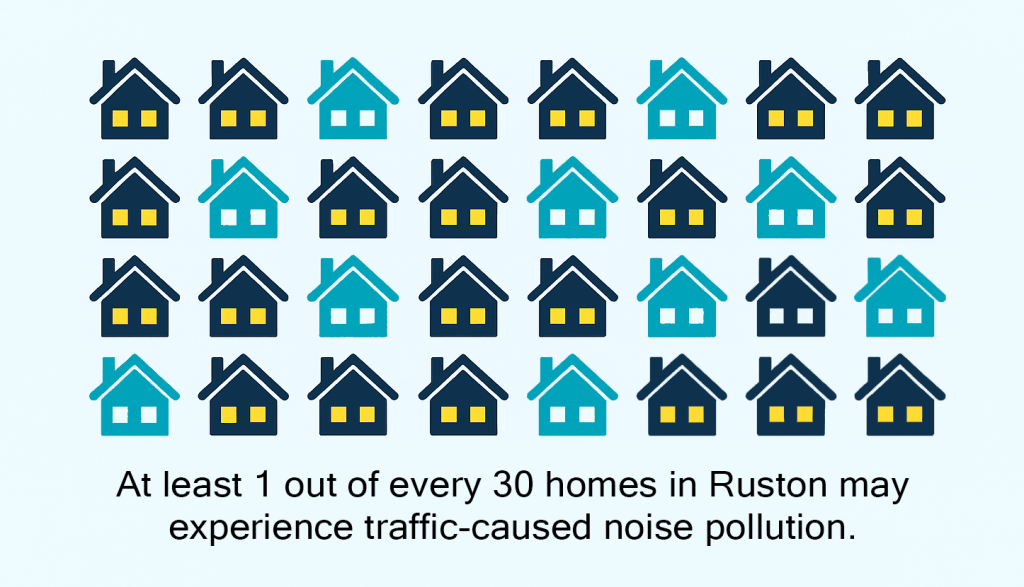

Local census data says we have about 8,500 homes in our community. Of those homes, 30% of them are as close as our house is to a major noise source like Hwy 167. That is over 2,500 homes that have negatively impacted quality of life due to a lack of effective sound pollution prevention.

And unlike water or trash, noise isn’t routinely measured or planned for by city governments. Without putting intentional strategies in place, the loudest parts of a town typically only get louder.

As intrusive noise levels rise, residents with the resources to relocate often move farther out of town, eroding the local tax base and shifting neighborhood dynamics. This leads to more transitional renters who, though not inherently disengaged, tend to have fewer reasons or opportunities to invest long-term in the area.

PART 2: Let there Be (Less) Light

I used to live next to a school parking lot that was occasionally used for drag racing late at night. The powers-that-be decided to curb the young racers’ enthusiasm by installing lights that stayed on ALL night. Every night. All year. Once we could, we moved.

You can find you own town’s rating here.

Ruston currently has a Bortle Scale rating of 6.8, a tool used to measure light pollution. Anything above a five means backyard stargazing is limited, with 1 being a “pristine dark sky” and 9 being bright “inner city sky glow.” A 6.8 puts us in the “bright suburban sky” category, where only the brightest stars are visible. Things like the Milky Way? You’re not likely to see it here.

That’s not to say lighting is bad. Humans instinctively associate light with safety and darkness with danger. It’s primal; early survival depended on it.

Civic design from the 1960s onward followed the “more light = less danger” policy, building on the assumption that a brightly lit place is a safe one.

Overly bright streetscapes have negative consequences too, such as making neighborhoods less hospitable. Relocating like we did, is surprisingly common according to studies done by the London School of Economics. And in downtown areas, excessive lighting can shift a space from feeling safe, to feeling unwelcomingly on display.

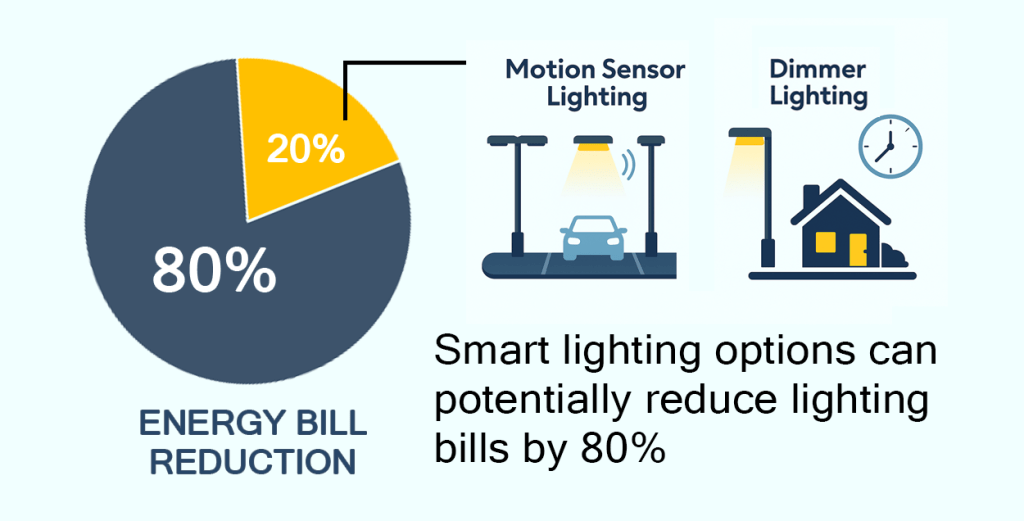

Over-lighting costs us literally as well. Let’s just say that the parking lot from my past had ten light fixtures. At 200 watts each, and $0.13/kWh (the current average cost of electricity in north Louisiana), that’s an annual energy consumption of $1,139 a year.

But what if that parking lot had been equipped with motion sensor lights? The average light usage could be reduced by 80%, cutting that $1,000-plus bill to about $200 a year.

Upfront these upgrades cost about $100-200 more per a fixture. So for that 10-light parking lot, adding motion sensors would raise the initial cost by $1,500–$2,000. But sensors can also prolong the life of the light bulb by five to ten years, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, resulting in less maintenance, less disruption, and less energy waste.

Now apply that math to every city or parish-funded parking lot with fixtures on a similar lighting plan. In theory, over $10,000 in annual power bills would drop to $2000.

This kind of cost reduction benefits both public and private sectors. But energy use is only part of the equation. The color temperature of light matters as well.

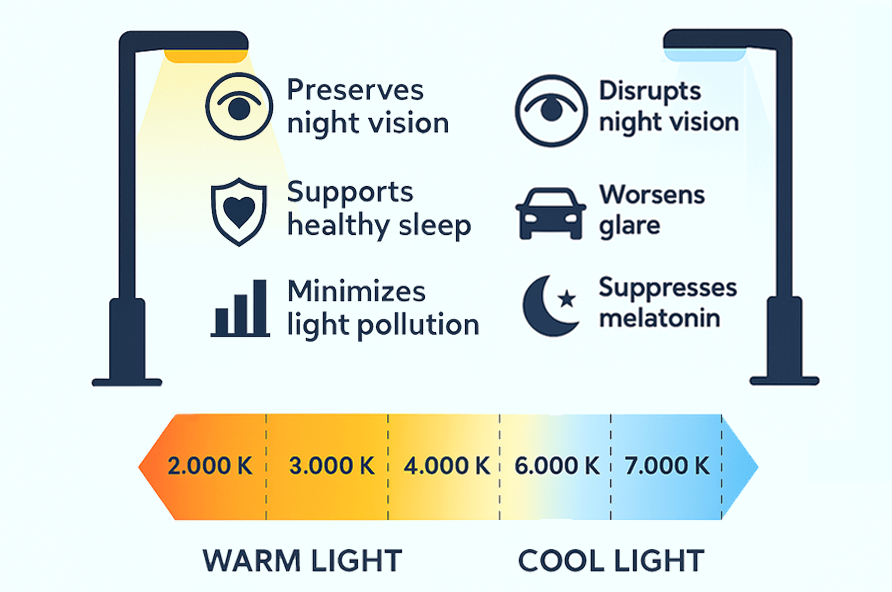

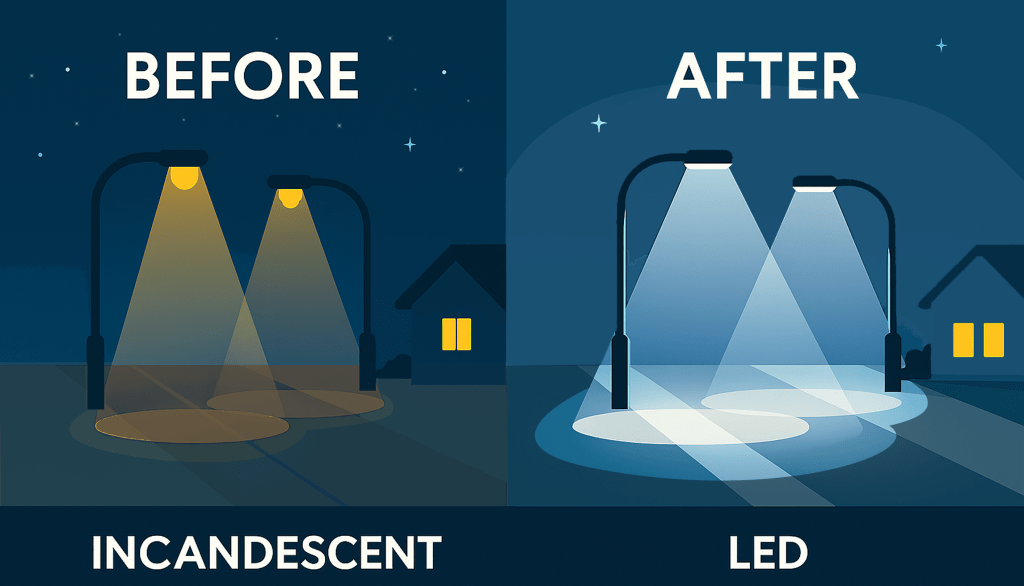

Most modern LED streetlights emit a cool-spectrum, bluish-white light. They look brighter but it come with tradeoffs:

• Blue light disrupts night vision more than warm light. That harsh “screen glow” we’re told to avoid? Modern society put it everywhere, sorry folks.

• Blue light worsens glare, especially for older drivers and those who have had eye surgeries.

• Blue light suppresses melatonin, disrupting natural sleep cycles.

• Blue light washes out the night sky more. So long, stars.

In contrast, warm-spectrum LEDs are softer on the eyes, more biologically compatible, and still highly energy efficient according to studies done by Harvard University.

So why don’t we use more of them? When warm LEDs first hit the market, they were more expensive and less efficient. That price gap has narrowed, but the old perception lingers, while some cities are playing catch-up installing warm lighting as old cool LEDs burn out.

Then there is the actual brightness of the bulb. Many cities didn’t account for the improved performance of LEDs when they upgraded older lighting. One high-efficiency LED can match the light output of two or even three older bulbs. Swapping fixtures one-to-one, and keeping the same pole heights resulted in well-lit streets that suddenly became overly-lit ones; a change that was welcomed without fully understanding the long-term consequences.

When we talk about light pollution, color temperature, intensity and light spread are big players, but let’s not overlook the simplest fix of all: point the light down, not up.

Whether it’s floodlights on a business sign, “safety lights” illuminating a wall, or lights shining up trees, upward-facing lights create glare, further obscure the stars, and spill across yards and windows where it doesn’t belong.

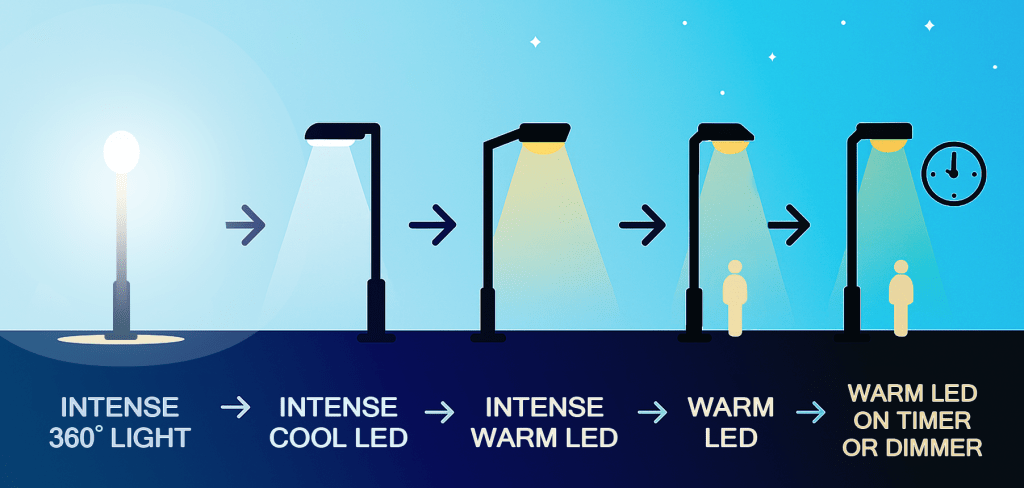

Progression from most light pollution-causing-lighting to least.

Good security lighting illuminates only the areas needed, avoids casting harsh shadows criminals can hide in (although it’s great for hide-and-seek), reduces contrast blindness, and doesn’t blind passersby or drivers.

Yes, a glowing building or tree look cool. But one that glows intensity all night, year-round, and can be seen from over a mile away? That may be a bit much. Even simply converting up-lighting to warmer or to a less intense bulb can go a long way.

So if we think we may have sound and light pollution problems, what can we do about it? We will explore what other communities are doing in the next installation of this article.

PART 3: Let There be Peace

After reading part one and two of this article, you may be thinking; ok, maybe sound and light pollution affect me, but how do communities address these issues?

Often the best place to begin is with collecting data. Whether you’re trying to update city lighting, establish new noise ordinances, or design friendlier residential areas, a local audit gives you a foundation to make a case.

Louisiana has some built-in funding avenues that can support this kind of work:

Energy Efficiency & Conservation Block Grants (EECBG) from the Louisiana Department of Energy & Natural Resources: The program supports planning for energy upgrades, conducting audits, installing renewables, and more. With awards ranging from $100,000–$200,000, it’s an ideal opportunity to guide future ordinances and civic improvements.

The Louisiana Public Entities Energy Efficiency Program from the Louisiana Public Service Commission: Since 2017, this program has awarded over $80 million to schools, parks, and local governments, largely for lighting upgrades. The program focuses on infrastructure improvements, so it’s a great resource to look to after studies are done.

Louisiana Department of Transportation & Development Highway Noise Policy: While not a grant in itself, the Louisiana DOTD maintains a formal Noise Policy, 23 CFR Part 772, that states any major federally‑assisted road project must evaluate noise impacts and consider abatement if thresholds are exceeded. The policy serves as a good roadmap and a lever when applying for funding or advocating for buffers.

Programs like the EPA’s Community Change Grants provide funding to address environmental justice concerns, including noise pollution. Projects could include purchasing affordable sound meters, hiring acoustic consultants, or partnering with local colleges for student-led studies and solutions.

Even without formal funding, studies can begin simply: a weekend community event, volunteer recordings, or crowd-sourced sound and light logs.

Once studies are complete, the next step is to identify what methods of mitigation are best for our area, and where to begin implementing them.

The following are the most common means of sound and light pollution mitigation:

SOUND

1. Noise Barriers: Walls or earth berms built along highways, railways, or industrial zones can reduce noise levels by 5–10 decibels or more.

2. Zoning and Buffer Zones: Separating residential areas from noisy uses (like airports or heavy industry) Buffers like greenbelts, open space, or commercial zones between noise sources and homes.

3. Quieter Road Surfaces: Porous asphalt and rubber-modified pavement can reduce tire noise. Maintenance also matters, worn or grooved pavement increases noise.

4. Speed Limit Reductions: Especially in urban corridors, lower speeds reduce engine, tire, and aerodynamic noise. A cheap fix, minus a few speeding tickets.

5. Enforcement of Vehicle and Equipment Noise Standards: Limit over-loud mufflers, construction equipment hours, and the like.

6. Urban Tree Canopy and Vegetation: Trees alone don’t block significant noise, but layered vegetation can provide relief.

LIGHT

1. Full-Cutoff or Shielded Fixtures: Outdoor lights that direct light downward, not outward or upward.

2. Warm-Temperature LED Lighting: We covered this one.

3. Dimming and Adaptive Lighting: Time-based dimming after midnight in low-traffic zones.

4. Light Curfews: Regulates how long signs, building lights, or decorative lights can stay on overnight, especially in business districts.

5. Zoning Codes and Lighting Ordinances: Specific requirements for light trespass, lumens per acre, or brightness limits by zone type.

6. Public Awareness Campaigns: Education around “light responsibly” or “quiet zones” can encourage community investment and improvements.

Cities often reexamine their sound and light ordinances first. Some cities even create zones for lighting and sound protections. For example, areas where lights are dimmed at sunset, or have motion sensors. Or zones where raised land berms must border heavily-used roads to protect surrounding residential use.

Ordinances often lack the level of detail needed to give people a legal process by which to respectfully request protections from noise or light pollution in their backyards, so the process of enforcing ordinances should be clearly outlined and available to the public as well.

Other ideas include positive over negative reinforcement, like awarding or celebrating businesses and citizens for improving lighting and sound mitigation.

Whatever a town does, meaningful change requires both civic and individual action. While earth berms may reduce noise for nearby homes, neighbors can choose quieter tools, or not to engage in loud noises before 8am or after 6pm. Small business owners can choose to turn down or turn off a flashing sign that shines into residential neighbors’ windows, or install lights that shine down, without an ordinance telling them to.

We are all going to be a little noisy or bright sometimes, why Christmas is the perfect example with the great lights and busy roads this time of year. The goal of sound and light pollution mitigation isn’t to plunge cities into mute darkness, but to improve its quality of life, foster respect for neighbors, and care for the environment we share. A great way to make room for a little peace, and goodwill towards all.

Leave a comment